Ways to Develop Your Practice through Self-Reflection

Most teachers will be familiar with the concept of learning as a process, something that is never completed, and this belief is frequently presented to students in relation to their language learning. But as much as this applies to students, it applies to teachers too: learning to teach is never ‘finished’. As well as keeping up to date with developments in teaching methodologies and approaches, teachers can further their own development and become better and more effective teachers by regularly reflecting on their own classroom practices.

Ultimately, we all want to be better teachers. We want to help our students get to grips with and learn the language in the most efficient and effective ways possible. While we’re all familiar with the feeling of having taught a great lesson, or with a lesson having not gone very well, and will have spent time discussing what happened with colleagues, unless we have the means by which to reflect on and analyse what led to our successes or failures, we risk repeating the same mistakes. It is not enough to teach in a particular way just because if ‘feels right’ or because we’re in the habit of doing so, and reflection is the ‘sole method of escape from the purely impulsive or purely routine action’ (Dewey, 1933).

In recent decades, education has seen a significant rise in the practice of self-reflection as a means of professional development. Reflection involves ‘intellectual and affective activities in which individuals engage to explore their experiences in order to lead to new understandings and appreciation’ (Boud, Keogh, and Walker, 1985). But in order to be useful, reflection needs to be organised, focused on a specific area or areas, and consistent. Teaching and learning are complex, and as a result it is ‘difficult to reflect without some kind of evidence’ (Walsh & Mann, 2015). The activities described in this article offer ways of collecting such evidence in order that we can better reflect on our practice and enable us to develop as teachers, leading to more effective and successful outcomes for our students.

For each of these activities, to be most effective they should be carried out a number of times, and ideally with some regularity, so that the findings can be compared and evaluated to give a more consistent picture of what’s happening in your classroom, and why. It’s also valuable to undertake both ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ reflection, with hot reflection taking place immediately after a lesson, and cold reflection taking place after a day or two. Each can reveal different insights, as the immediacy of hot reflection means we can clearly remember details, but is often influenced by our feelings about what happened, whereas cold reflection allows more processing time and so can lead to more objectivity, and place our findings within the wider context of a course or syllabus.

Activities and Frameworks for Self-reflection

Lesson Reflection Wheel

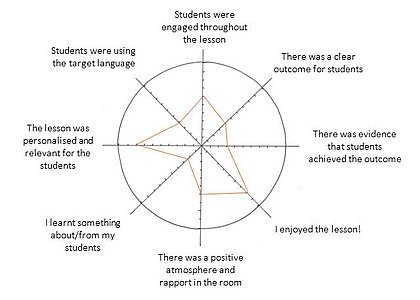

A lesson reflection wheel enables us to focus and reflect on different, specific aspects of a lesson, and acts as a launchpad for discussion and deeper reflection with a colleague. Draw a circular framework like the example here, divided into eight segments. Along the lines of each segment, mark ten points. Take some time to think about what factors you believe contribute to an effective lesson, and write these around the outside of the circle (below are my examples, but yours may differ!)

After a lesson, use the framework to reflect by following these steps:

- With the central point of the circle being zero and the outside being ten, mark the degree to which you feel the lesson succeeded in relation to each of the eight factors. Join the dots together.

- Write down, or record audio notes, about what happened in the lesson that contributed to the rating you’ve given each of the factors.

- Discuss your completed framework and notes with a colleague. If possible, do this as part of a peer observation programme and ask your observer to complete the same framework about your lesson.

- Consider what you might do in future lessons to improve the areas you feel were least successful.

- Repeat the process over a series of lessons, ideally with the same group, and compare the results. Consider what has changed during the process, and why

Fridge; Suitcase; Bin

Fridge; suitcase; bin is a simple model for quick and regular reflection, but also works well as a follow up to the other activities described in this article. At the end of each lesson, identify what you want to put in the fridge, in your suitcase, and in the bin. The item you put in each can be anything that happened in the lesson, from a specific activity or approach, to a way of explaining or demonstrating something in the class or an instruction you give to your students.

Fridge - something you want to keep to use again at a later date

Suitcase - something you want to carry with you and use again soon and/or frequently

Bin - something that didn’t work for you, that you may want to avoid in future lessons

The Blob Tree test

The Blob Tree test was first created by behavioural psychologist Pip Wilson in the 1980s, and has since been used in countless ways and contexts. It’s a framework I often use in class with students, but it can also be a useful tool for self-reflection. Each of the ‘blobs’ in the tree is in a different position and a different ‘mood’. In relation to self-reflective teaching practice, we’ll imagine that the tree represents the lesson as a whole. After a lesson, or if possible at set points during a lesson, look at the tree and consider the following questions:

• Which ‘blob-person’ on the tree best represents how you feel about the lesson (so far)?

• What happened, or is happening, in the lesson that contributed to your choice?

• What would need to happen / have happened for you to feel differently?

The Weather Model

The Weather Model was originally developed by a group of students in collaboration with Maclean (2016) in the field of social work, as a means to facilitate critically reflective practice. The underlying concept is that the weather is something English people talk about every day, and so the model is something that should be used as often as possible. Here I’ve adapted the questions for teaching practice:

Sunshine: What went well in the lesson/task? What was successful?

Rain: What didn’t go so well? What was challenging?

Fog: Was there a point where you couldn’t see clearly, or weren’t sure what to do?

Snow: Was there something you saw differently during the lesson? What was it?

Lightning: What came as a surprise?

Wind: Did anything change the course of the lesson, or cause you to change what you had planned to do?

Storm: Was there any conflict during the lesson? What caused it? How did you respond to it?

Reflection is about ‘learning through and from experience towards gaining new insights of self and practice’ (Finlay 2008). But there is a danger that where reflection is ad-hoc, any insights we gain may be lost amongst the countless other things we have to think about as teachers. Structured activities like those above, and even more in-depth reflective and developmental projects, lead to more effective outcomes and positive impacts on our development as teachers. Edward Russell’s ‘Situation-Puzzle-Response-Evaluation’ (SPRE) format is an excellent example of a more in-depth exploration and reflection project, and provides a clear and effective structure for organised development in a specific area identified by the teacher. It includes emphasis on the collection of evidence for systematic reflection, and ‘can lead to significant impact, action and learning’ (Russell 2019).

As well as being evidence based and organised, reflection should also be collaborative. There is enormous value in sharing one’s observations and thoughts with a peer, as dialogue and collaborative discussion can lead to deeper and richer insights. For each of the activities described above, try to make time to discuss your reflections with a colleague. Where possible, ask a colleague to observe a lesson for which you’re carrying out a self-reflection activity, and where relevant, have a colleague undertake the same activity themself in their own lesson so that experiences can be shared in a structured and organised way.

References and Further Reading

Boud, D., R. Keogh, and D. Walker. 1985. ‘What is reflection in learning?’ in D. Boud, R. Keogh, and D. Walker (eds.). Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning. London: Kogan Page Ltd.

Dewey, J. 1933. How We Think: A Re-statement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Education Process. Boston, MA: DC Heath & Co.

Finlay, L. 2008. Reflecting on ‘Reflective practice. Practice Based Professional learning Centre, The Open University: paper 52, January 2008.

Maclean, S. 2016. A new model for social work reflection: whatever the weather. Professional Social Work, March 2016: pp28-29.

Russell, E. 2019. Situation, Puzzle, Response, Evaluation (SPRE): A Discoursal Panacea? in IATEFL Teacher Training and Education SIG newsletter, April 2019.

Walsh, S. & Mann, S. 2015. Doing reflective practice: a data-led way forward in ELT Journal, Volume 69/4, October 2015.

Wilson, P. & Long, I. 2018. The Big Book of Blob Trees. Abingdon: Routledge.

About the Author

Jade Blue is an English language teacher, trainer and materials writer, who teaches and delivers training workshops and seminars in Europe and Japan. Her primary research interests focus on learner-generated visuals in ELT and learner autonomy. She has presented at IATEFL and as a Keynote speaker at The Image Conference. Jade writes her own reflective ELT blog, has been published in Voices and English Teaching Professional, and has contributed to a Routledge publication on Reflective Practice in ELT.

Learn more about Skillful 2nd edition and see how it develops student’s confidence & communication skills