Scaffolding learning in the Primary classroom

Introduction

‘What a child can do today with assistance, she will be able to do by herself tomorrow.’ Lev Vygotsky

Isn’t it wonderful when you see pure joy and excitement from a child learning English for the first time? Their eyes sparkle as they sing new songs and test out their first English greetings at the school gate!

However, in order to maintain this enjoyment and enthusiasm for learning, children need to feel supported as new linguistic challenges appear. It’s easy to forget the different ways in which children learn and understand instruction, assuming, for example, that all first graders will manage a task in a similar way.

Challenging while supporting

As educators, it’s important to constantly think and plan how to actively support our students so that they can become confident users of English.

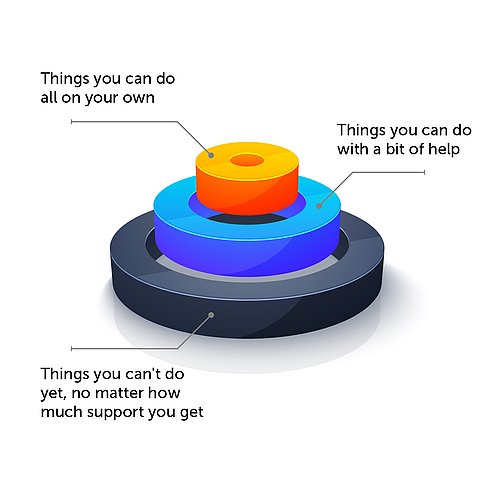

We should always try to challenge our students by presenting them with tasks that are just outside their comfort zone but not impossible to do, as referred to by Lev Vygotsky and his zone of proximal development (ZPD).

‘ZPD is the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers.’ (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86).

Scaffolding learning

You may have already heard about the educational strategy called scaffolding, a theory of instruction devised by Jerome Bruner in the 1970s. This is a support system that engages students in the learning process and helps them reach their learning objectives. The teacher acts as a facilitator by introducing clear and helpful steps that work as a temporary bridge between the student and a new concept or skill. Scaffolding is vitally important in the early years as children develop skills (learning to learn), slowly building their confidence until they are able to work on the tasks independently.

Bruner was interested in early childhood development and, in his studies, he observed the many ways in which mothers interact with their children, explaining as follows: ‘In such instances, mothers most often see their role as supporting the child in achieving the intended outcome, entering only to assist or reciprocate or “scaffold” the action’ (Bruner, 1975, p. 12). In the classroom, there are many natural ways we may help and support our students’ learning too.

What does scaffolding look like in the classroom?

We can define scaffolding as two main types: soft scaffolding and hard scaffolding.

- Soft scaffolding might see the teacher walking around the classroom helping students as they work and as their doubts appear, giving tips, pointing to specific things in their books, writing extra words on the board, or hinting at a word by voicing the first few letters.

- Hard scaffolding will see the teacher using graphic organizers, visuals and worksheets to take the students systematically through an activity, using specific prompts as they work. These will be based on typical learner difficulties and specific needs.

We can help students individually, or as a whole class, using the following critical process:

- Modelling: I do, you’ll watch

- Guided practice: I do one, you’ll help

- Gradual release: You do one, I’ll help

- Independent practice: You do one, I’ll watch

Teachers will need to know what each student is capable of and plan scaffolding strategies accordingly. This can be a lot of work for the busy teacher but thankfully, there are materials that bring a solid scaffolding approach like the Macmillan course for young learners, Global Stage, for example.

Once we start to understand how scaffolding works, we can apply different strategies at different moments of our lessons.

We can:

- establish clear classroom routines so children know what to expect and what comes next.

- install wall displays with pictures, key words and structures.

- promote a culture of curiosity and discovery by having a place to seek more information in a book corner in the classroom.

- activate students’ prior knowledge by using open-ended questions to ignite curiosity, for example, What do you think would happen if …?

- always give students enough time to think, respond, ask new questions and encourage good group listening skills.

- physically demonstrate words by miming an action, showing real objects or using flashcards.

- regularly promote pair and group work where students share ideas and learn from their peers.

- monitor, give feedback and encourage a culture of learning through mistakes.

- apply formative assessments to identify when and where to scaffold.

If you teach using the scaffolding, Global Stage supports students’ growth into competent speakers and writers of English, and caring, responsible citizens fully prepared to succeed as the leaders of tomorrow’s this approach throughout the course.

True involvement

There is a lot of truth in this old proverb:

‘Teach me and I will forget, show me and I may remember, involve me and I’ll understand.’

We often scaffold learning in an intuitive way like showing a toddler how to build a tower of wooden blocks, then watching them try on their own.

In the classroom, the attentive teacher will know which students need more time on a task, what they have understood so far and when to recap on an instruction.

When we involve our learners in a dynamic process by giving them carefully planned stepping stones through multiple techniques, learning outcomes are at a considerable advantage.

Positive feedback is essential too. When you build up trust between yourself and your students, it is more likely that you will have a classroom where children feel safe to make mistakes. Understanding the ‘why’ of those mistakes can be crucial for the child’s linguistic development.

Giving learners positive feedback and emotional support will also encourage them while scaffolding, especially when concepts are complex. They will need to be given extra chances to improve, learn from mistakes and try again.

Conclusion

Scaffolding learning therefore is a reciprocal process, taking place through interactions with the help of a more knowledgeable other. It’s never ‘just a task’, it’s the gradual development of a learner’s thinking and learning process. When done gently and with respect to the learner’s uniqueness, this journey can be so much more enjoyable.

When needs are matched to the learner, we put them in a position where success is achievable and that is a very empowering feeling, right?

References

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978) Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J.S. (1975) From communication to language: A psychological perspective. Cognition 3, pp. 811–132.

Gibbons, P. (2015). Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning: Teaching English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Lucy Crichton graduated in Drama, Art and Design and Teaching English as a Foreign Language. She has been a teacher for 28 years and during that time have also been involved in teacher training. She writes for the primary classroom and these projects have taken me to countries in South America, Europe and Asia. Lucy is the founder of The Secret Garden English School in Florianopolis, where she teaches children and teenagers with a focus on living the language through practical projects, music art, drama, gardening and cooking. Brazil is her adopted home.

Learn more about Global Stage and see how it develops student’s confidence & communication skills