Mediation Tasks for Young Learners

Mediation

Mediation is making a slow but steady appearance in the ELT world. However, most of the materials that have been developed so far target only one type of learner: the adult student.

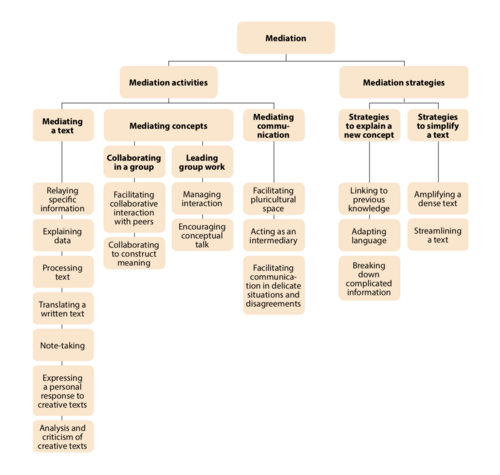

In the CEFR, mediation is defined as any time someone ‘acts as a social agent who creates bridges and helps to construct or convey meaning, sometimes within the same language, sometimes from one language to another’ (Council of Europe 2020:90). The language activities and the corresponding scales identified for this skill are grouped in three macro categories:

- Mediating a text: using one's own words to pass on information to someone who does not have access to it;

- Mediating concepts: sharing ideas and working with others to reach a solution;

- Mediating communication: helping others understand each other by bridging sociocultural differences.

[Pic. 1/1: grid of Mediation activities and Mediation strategies from Companion Volume with New Descriptors (Council of Europe, 2020:90)]

Do young learners already engage in any of these activities? Here are some examples that I have noted down during an ordinary teaching day at the school where I work in Spain:

- an 8-year-old Chinese student translating to her mother, who does not speak Spanish, the content of a leaflet advertising a new guitar course at the school (i.e. Mediating a text: Translating a written text in speech)

- a group of 12-year-old students discussing ideas to organise work for their science project (i.e. Mediating concepts: Collaborating in a group)

- a 16-year-old Mexican student explaining to his Spanish classmates and teacher the difference between Mexican and Spanish tortilla (i.e. Mediating communication: Facilitating pluricultural space).

Benefits

Young learners already act as ‘mediators’ when discussing texts, collaborating and communicating meaning, both in class and in those contexts that are familiar to them. Nonetheless, including mediation in the language classroom would provide additional practice for students to reflect on and learn how to make the most of their language to achieve the desired effect on their target audience when involved in such situations.

By practising mediation in class, students would also learn the ropes of how to engage in cross-linguistic and cross-cultural communication. The Chinese child translating for her mother and the Mexican teenager comparing dishes, are more likely to be aware of how to overcome linguistic and cultural barriers than most of their peers. Therefore, presenting young learners with activities in which sociocultural mediation is necessary–such as act-outs, debates and role-plays to mention a few–would be an effective way to broaden all the students’ plurilingual and pluricultural repertoire.

Finally and most importantly, mediation as described in the CEFR could serve as a ‘hub’ connecting useful strategies for young learners to develop and use 21st century skills. When involved in a mediation task, language users are naturally brought to receive and produce texts (i.e. literacy skills), negotiate meaning, formulate hypotheses and suggest alternatives (i.e. learning skills), as well as to be flexible and take initiative (i.e. life skills).

Mediation Tasks for Young Learners

The example tasks proposed in this section take as their starting point the scales for mediation included in the 2018 update of the Collated representative samples of descriptors of language competences developed for young learners. The descriptors, and the corresponding tasks, are aimed at two of those age groups underrepresented in the CEFR: from age seven to ten, and students from age 11 to 15.

| Relaying specific information in speech/writing | |

| A1 Can relay simple, predictable information about times and places given in short, simple statements. | A2 Can relay the point made in short, clear, simple messages, instructions and announcements, provided these are expressed slowly and clearly in simple language. |

| Age: 7-8 | Age: 11-15 |

| Task | |

| Explain situation: You are at the train station with your grandparents. You hear this message, but your grandparents don't understand. What does the message say?

Organise class into pairs (A: grandchild; B: grandma/grandpa). B covers their ears. A listens to the announcement and relays information to B. B can ask A for repetition as necessary. | BEFORE TASK: Organise class into small groups. Assign each group to watch a different YouTube video tutorial (e.g. how to make ‘homemade slime’, cook brownies or organise a wardrobe). Students watch tutorials at home and make notes.

TASK: Students regroup, put their notes together and use these to prepare a short presentation. Students from other groups take notes and ask speakers to repeat and clarify as necessary (during or after presentation). |

| Comments | |

| - Use visuals to support your instructions: draw or find photos of a train station platform, an elderly couple, a boy or girl, PA system loudspeaker, etc.

- You can find recordings of authentic announcements on YouTube (e.g. train station: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2LEnabZYJ64).

- To adapt the language to your students’ level/age, record your own version of the announcements on your phone and use these instead.

- Use simple role-play situations to go with any of the announcements you find/create (e.g. ‘family at the train station’, ‘foreigners at a small airport’, etc.). | - To adapt the instructions to your students’ level, instead of videos, you could: 1) use written lists of instructions or 2) record your own instructions on your phone or 3) make your own video tutorials. The advantage of using written lists is that you can run the whole activity (both reception and production) in class.

- Instead of giving a presentation, students could text, email or voice-message a friend. |

| Language | |

| - Telling and talking about time (e.g. The train leaves at three/is late); - Asking for repetition (e.g. Can you repeat, please?) | - Explaining unfamiliar concepts/objects (e.g. it’s made of); - Sequencing (e.g. then |

| Explaining data in speech/writing | |

| B1 Can describe in simple sentences the main facts shown in visuals on familiar topics (e.g. a weather map, a basic flowchart) | B2 Can interpret and describe reliably detailed information contained in complex diagrams, charts and other visually organised information on topics in his/her fields of interest. |

| Age: 10 (Descriptors available for B1) | Age: 14-15 (Descriptors available from A2 to B2) |

| Task | |

| Organise class into groups (A, B and C). Give group A diagram 1 (the water cycle), B diagram 2 (the carbon cycle) and C diagram 3 (the nitrogen cycle).

Students look at information in their diagram and each group prepares a short presentation on their topic. Monitor and help as necessary. Groups give their presentations and students in the audience take notes and ask speakers to explain/clarify as necessary. | Explain situation: In your class you have been discussing (e.g. ‘video game addiction’). Your English teacher has invited you to write an informal article on this topic for the school magazine.

Organise class into pairs. Give each pair a graph showing data about the selected topic (e.g. a bar chart showing percentages of most affected age groups/countries, or an infographic illustrating symptoms /advantages and disadvantages of playing video games).

Pairs analyse, discuss and, together, they select data in the graph to incorporate into their article. |

| Comments | |

| - For lower-level/younger students, use or create simpler graphs (e.g. bar charts showing results of a class survey on children’s favourite foods, sports or books). | - Higher-level/older students could analyse the data in the graphs on their own, compare with a partner and then write the article individually. |

| Language | |

| - Clarifying (e.g. This means…) and asking for clarification (e.g. Can you explain what/how...?); - Explaining processes (e.g. It turns/changes into). | - Giving opinions (e.g. I reckon); - Recommending (e.g. It might be a good idea if/to…). |

| Translating a written text in speech/writing | |

| A1 Can provide an approximate spoken translation into (Language B) of short, simple everyday texts (e.g. brochure entries, notices, instructions, letters or emails) written in (Language A). | A2+ Can provide an approximate spoken translation into (Language B) of short, simple everyday texts (e.g. brochure entries, notices, instructions, letters or emails) written in (Language A). |

| Age: 8-10 | Age: 14-15 |

| Task | |

| Explain situation: You are at the public swimming pool. There is a family of tourists outside. They are reading the swimming pool rules, but they don’t understand (students’ L1). Help them understand.

Organise class into pairs (A: tourist; B: e.g. Spanish boy/girl). Give A a list of swimming pool rules written in (students’ L1). Students act out the situation: A translates rules for B. B is not allowed to read the rules so he or she will be able to ask for repetition as necessary.

Swap roles giving B a different list of rules written in (students’ L1). | Explain situation: Your summer course in the UK has almost finished. Your mother, who doesn’t speak English, has just sent you the email below in (students’ L1). It’s for your host family. Provide a rough translation of the email for them.

Organise class into pairs (A: e.g. Spanish student; B: homestay father/daughter, etc.). Give A email in (students’ L1). A reads email and summarises the key information in English (e.g. whether the mother has written to thank the host family, invited them to stay in touch or explained a problem). B asks for clarification and/or repetition as necessary.

Swap roles giving B a different email written in (students’ L1). |

| Comments | |

| - Students are not supposed to translate the source text, but rather summarise the content of the texts using their own words in English. | - Try and find or create your own texts that include sociocultural elements like food, habits, traditions, etc.

- To set this task as homework, students could record a speech on their phone or tablet and send it to you via email. |

| Language | |

| - Talking about permission and obligation (e.g. You have to wear…); - Backchanneling (e.g. Right) | - Reporting speech (e.g. She asked if you could...); - Explaining unfamiliar concepts/objects (e.g. It looks like |

Scaffolding

To prepare for a mediation task, students/mediators need to develop a variety of strategies and knowledge.

- Strategies to tackle source texts

The first step to take in a mediation task is to identify key information in a source text. Depending on the students’ age and level, texts will be shorter or longer, and strategies more or less sophisticated. Teenagers could be asked to find key points in a written text and underline or summarise them in a short list in their notebooks. Younger students, on the other hand, may find it easier to choose the key point or points from a given list of options, or to answer ‘true or false’ questions. Likewise, when dealing with oral source texts, older students might be able to take notes in a more proper fashion, whereas primary students–although still able to listen and write down specific words, phrases and numbers–would need more support, for example by completing gapped notes, drawing or even colouring in items.

- Strategies to produce target texts (Mediation strategies)

The second step is to pass on the key information selected in the source text to the target audience through a target text. In the process, students/mediators may need to explain, paraphrase, summarise and/or translate information.

To train students to explain information, teachers could guide them to discover the strategies that writers and speakers employ when they clarify concepts, expand on what they write or say, exemplify and so on. Students from age seven to ten, for instance, could be trained to give examples or use their body language by using simple matching, sorting or TPR activities. Conversely, older students will be better able to understand and use more complex analogies, as well as adapt their language to a given situation, such as when explaining a difficult concept to–or even adapting a book or film for–a younger child (e.g. by rewriting the concept or plot into a fairy tale for children).

For summarising and paraphrasing information, primary students could read a short text (or paragraph or part of it) and then choose from a given list the sentence that best summarises or paraphrases it. On the other hand, secondary students might be better able to handle sentence transformation exercises or to learn how to use the dictionary or thesaurus more effectively (e.g. by focusing their attention on the different levels of register or frequency of a lexical item).

Sometimes the information in the source text is in the student/mediator’s first language. When involved in cross-linguistic mediation, students/mediators need to know that they are not supposed to translate the source text word for word, but rather relay the key points in the source text in the target language. Both children from age seven to ten years old and teenagers from 11 to 15 years old can be trained with simple multiple-choice questions. The first age group could concentrate on simpler concepts, individual words or small chunks of language. Older students, however, could focus on more challenging shades of meaning or levels of register. For example, they can be presented with different versions of translations of a text or a paragraph and asked to choose the one that best matches the context and the target audience.

For students to produce target texts, they need to know the genres they belong to. When students are exposed to texts in class–be they short and simple conversations or emails between friends for younger and lower-level students, or subtler and more complex academic lectures or essays for older and higher-level ones–teachers should also focus their attention to the conventional genre features, such as their purpose (e.g. Why did Joanna write this email?), organisation (e.g. How many paragraphs did she write? What does she say in the first paragraph?) and language (e.g. Find three synonyms for “but” in Joanna’s email).

- Sociocultural knowledge

Source texts might include references to cultural elements. These references might be familiar to the students/mediators, but not to the target audience (e.g. a typical dish, a traditional ceremony or a historical place). To help students develop sociocultural knowledge, besides exposing them to cultural content, teachers could have them ‘experience’ cross-cultural situations through role-play. Students could be asked to play act or improvise scenarios in which they have to explain something specific to their own culture (or one they know about) to someone else who does not have access to the same cultural repertoire.

- Language

It goes without saying that to produce texts, learners will also need to know how to use language. Teachers can teach useful language (e.g. vocabulary, grammar, functional language) before students do a mediation task (i.e. focus on forms) or after they have tried to complete or have completed the task (i.e. focus on form). Nevertheless, mediation tasks can also be used as final projects or consolidation activities for students to reuse the language learnt from the lesson, unit or term.

Conclusion

Children and teenagers attending school today are bound to come of age in a time in which certain skills will not be optional anymore. Practising mediation in class with appropriate tasks can help them widen their range of valuable communication strategies and knowledge and find their place in the 21st century.

References

Council of Europe, ´Collated representative samples of descriptors of language competences developed for young learners (aged 7-10 and 11-15 years) [https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/bank-of-supplementary-descriptors], 2018.

Council of Europe, ‘Common European framework of reference for languages: learning, teaching, assessment: Companion volume’ [https://rm.coe. int/common-european-framework-of-reference-for- languages-learning-teaching/168074a4e2], 2020.